Integrators are the New Generalists

reimagining the generalist-specialist dichotomy, part two of my complexity series

The generalist vs. specialist debate dominates modern career advice. When Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World came out in 2019, I devoured it up alongside the typical Silicon Valley canon: Atomic Habits, Outliers, Sapiens, Lean Startup, Zero to One. As a product manager without any specialization, I gravitated towards the notion of being a generalist. In my job, this mindset served me well. I could speak the language of designers, engineers, data scientists, finance, and customers.

But over time, legitimate concerns emerged. "Jack-of-all-trades" is only complete with "master-of-none". I feared staying at the surface while trapping myself going miles wide. But the real danger wasn't just about depth of knowledge. By identifying as a generalist, I became wary of deep commitment to any specific domain. Even when my curiosity beckoned me to enter the wander into unknown territory, my generalist mindset held me back, keeping me safe in my comfort zone.

My struggle reflects a broader debate. David Epstein's Range popularized the advantages of the generalist, elevating the perception of the "swiss-army knife" people. Notable figures like Bill Gates praised the approach, crediting Microsoft's success to teams with diverse experience and interdisciplinary thinking. Malcolm Gladwell offered a different view: His "10,000-hour rule" in Outliers shaped our perception of specialization. In his essay "The Hedgehog and the Fox", philosopher Isaiah Berlin proposed the idea of dividing thinkers into hedgehogs who view the world through a single defining idea, and foxes who draw on diverse experiences. McKinsey attempted to resolve this tension in the 80s with the concept of the T-shaped person: someone who combines broad knowledge with deep expertise in one area. Their solution was all Powerpoint, no punch—an elegant yet vague framework, but without tangible steps.

These models, while intellectually attractive, fail to capture the complex, unfolding nature of human potential immersed in a dynamic, interconnected world. Their greatest limitation isn't their prescriptions about breadth versus depth—it's their static view of time. Each model suggests that once you find your specialty or niche, you should stick with it. This fundamentally misunderstands human nature and modern society, where information flows freely, networks span globally, and career pivots happen without ever leaving your desk.

The key distinction lies between closed, defined systems and open, unstructured ones. Specialization makes perfect sense in bounded domains with fixed rules. Tiger Woods mastered golf because the parameters remain constant (and of course, through intense hard work among other things). But in 2024, we're operating in an increasingly complex, adaptive world where everything is constantly shifting. New types of work emerge daily while others fade into obsolescence. Consider the town crier, the lamplighter, or the milkman. Now, it's easy to imagine factory workers, truck drivers, and janitors being replaced by robots. But this tsunami of transformation isn't limited to blue-collar work. The landscape is shifting dramatically for knowledge workers too. When Google reports that AI now writes 25% of their code1, we must question not just which jobs will disappear, but what forms of work haven't even been invented yet. Today, specialization shouldn't be predetermined within existing structures. Instead, it should emerge organically from our own self-guided exploration.

I think about my friend Albert2 often. Back in high school, he shocked our Chinese-American community by choosing to stream League of Legends instead of going to college. I was drowning in AP classes and SAT prep, locked in with tunnel vision on the traditional path to success. Our friends’ parents would whisper in worried tones about this bright kid throwing his life away on video games. But Albert saw something none of us could see. He was intrinsically excited about a new emergent trajectory. While I was optimizing for college admissions, he was pioneering what would become a massive industry. His story captures why these rigid frameworks about specialization vs. generalization miss the mark. We need a more adaptive approach. One that integrates our evolving experiences, interests, skills, and opportunities as they unfold over time.

The Integrative Path

Instead of trying to force ourselves into rigid categories of generalist or specialist, hedgehog or fox, what if there was a third way? Enter Ken Wilber's Integral Theory, which offers a more nuanced perspective on how humans actually develop and grow. Rather than seeing breadth and depth as opposing forces, Integral Theory suggests we can transcend these apparent contradictions while including their valuable insights.

Applying Wilbur’s theory to the modern career debate introduces a new persona that I’ll call the Integrator. An Integrator transcends the traditional notion of disciplines altogether, moving beyond the artificial boundaries we've created between different domains of knowledge. They embody a dynamic approach where expertise isn't about accumulating separate skills, but about developing an ever-evolving understanding that naturally spans multiple areas. Instead of switching between specialist and generalist modes, they operate from a fundamentally different paradigm—one where knowledge and skills flow seamlessly across conventional boundaries.

The key principle here is "transcend and include". Evolution doesn't eliminate what came before, it builds upon it. Integrators excel at recognizing patterns across seemingly unrelated domains, quickly adapting their knowledge to new contexts, and synthesizing insights from diverse fields to create novel solutions. Their strength lies not just in their ability to learn new skills, but in how they carry forward and apply their accumulated wisdom to each new arena they enter.

I find this framing to be more flexible and gentle because of its inherent assumption about growth and evolution. Rather than suggesting we find our niche and stay there, it acknowledges that mastery in one domain often naturally leads to curiosity about others. As our expertise deepens in one area, we begin to recognize universal patterns that apply elsewhere, spurring us to explore new territories. This creates a self-perpetuating cycle of learning and integration that continues throughout our careers.

In practice, this might look like developing deep expertise in one area, then using that as a foundation to explore adjacent domains. Over time, you build what could be called an "evolving T" - where both the depth of your expertise and the breadth of your understanding continue to expand. The vertical bar of the T isn't fixed in one specialty but shifts and multiplies across different domains as you grow.

Integration in Action

In our modern achievement society, we idolize specialists like Tiger Woods, Kobe Bryant, Yayoi Kusama, and NVIDIA’s Jensen Huang. We also glorify generalists like Kanye West, Tim Ferris, and Oprah Winfrey. Yet for me, the most compelling pioneers are those who transcended this binary thinking altogether, generating breakthroughs by synthesizing wisdom across domains. These pioneers didn't merely collect skills or master single domains. They dissolved boundaries between disciplines entirely, following their curiosity beyond what was already discovered.

Ed Thorp stands as a titan cutting across domains, demonstrating how mathematical brilliance can transform entire industries through cross-pollination. Starting with physics experiments, he later revolutionized both gambling and finance by recognizing universal patterns in probability. Then, in collaboration with “father of information theory” Claude Shannon, he invented the first wearable computer to beat roulette in Vegas, transformed Blackjack card-counting into groundbreaking options theory, which led to him starting the first quantitative hedge fund. His wisdom extended to knowing precisely when to transition between domains—after winding down his hedge fund in 1988, he became the first investor in 22-year-old Ken Griffin's venture, which grew into the powerhouse Citadel. What I admire most is, unlike Elon Musk or Steve Jobs, Thorp achieved all this while maintaining excellent health into his 90s and nurturing a thriving family life—the true test of mastery lies in excelling across both personal and professional realms.

Leonardo da Vinci exemplifies the process transcending and including, where each domain enriched and informed the next. His apprenticeship with Verrocchio wasn't just about creating art—it trained his eye to observe the world with unprecedented precision. He secretly dissected human cadavers at night, sketching layers of muscles, organs, and bones with an artist's grace and a scientist's rigor. His anatomical mastery revolutionized how the human form was depicted in art, while simultaneously advancing medical knowledge by centuries—he was the first to accurately draw the human spine and discover the heart's four chambers. This synthesis of art and science flowed into his engineering work, where he designed flying machines based on his studies of bird and bat wings, and invented war devices like the tank and giant crossbow. Even his architectural designs transcended convention, using his understanding of human movement and proportion to reimagine spaces.

Francisco Varela's journey reveals how scientific inquiry can bridge seemingly disparate domains. While studying insect vision at Harvard, he discovered the self-organizing nature of living cells which is now known as autopoiesis. Rather than remaining in the comfortable confines of biology, Varela followed his curiosity into cognitive science, revolutionizing our understanding of how the mind and body interact. His theory of embodied cognition challenged the prevailing view that the mind was simply software running on brain hardware—instead showing how consciousness emerges from our dynamic interaction with the world around us. Through meditation, he discovered that contemplative traditions offered valuable methods for studying consciousness that Western science had overlooked. He then co-founded the Mind and Life Institute with the Dalai Lama to bridge Buddhism and modern science, pioneering neurophenomenology—an approach combining brain science with subjective human experience.

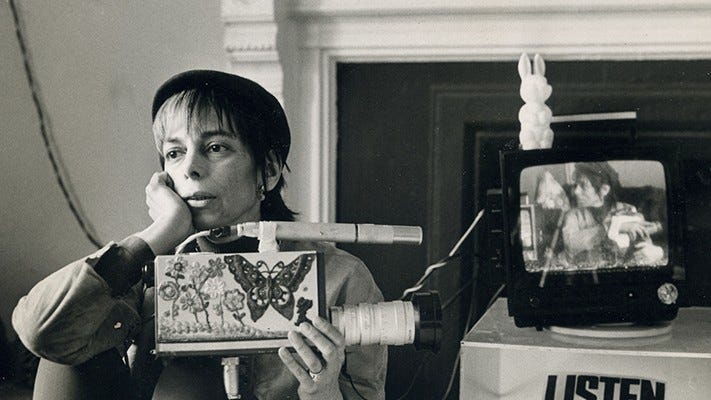

Filmmaker Shirley Clarke, hailed by Martin Scorsese as one of the "grand old masters of the underground," possessed a rare gift for transforming one art form through another. As a modern dancer in New York, she discovered her power lay in orchestrating movements rather than performing them, dissolving the rigid boundaries of traditional dance. When poor dance documentation frustrated her vision, she revolutionized filmmaking, emerging as the first American to unleash the full potential of handheld camera work. Unlike her contemporaries who either mastered a single craft or dabbled in many, Clarke dissolved the borders between disciplines entirely. She transformed experimental cinema by treating the camera as a dance partner, brought balletic precision to gritty street scenes, and infused documentary work with a choreographer's rhythm and flow. Clarke created a new artistic language that was neither dance nor film, but a seamless fusion of both. Her journey shows creative mastery isn't about pledging allegiance to a particular format or staying in your lane—it's about recognizing that true artistry transcends mediums and tools.

An Invitation to Evolve

In my own journey from computer science to product management to writing and coaching, I've discovered that each phase contributes to a richer whole. While any snapshot at a given moment might suggest I’m specializing, my arc reveals an ongoing story of continuous integration—not because I forced these connections, but because they emerged naturally when I stopped trying to fit into prepackaged boxes and predetermined trajectories.

For those of us in our 20s and 30s contemplating transitions, the usual narratives about finding your "second mountain", or having a mid-life crisis feel premature. We don't need a crisis. We just need permission to evolve, even if that means walking away from a path where we're already successful.

Take Ed Thorp, who went from outsmarting Vegas casinos to transforming Wall Street. Or Shirley Clarke, who evolved from dancer to filmmaker. Neither could have predicted their path while in the thick of it. They represent a refreshing third way—neither specialists like Tiger Woods who started golfing before walking, nor generalists like Tim Ferriss who pride themselves on rapid skill acquisition. They simply followed their genuine curiosity into the unknown, letting their path unfold naturally.

What if true specialization isn't about picking from a menu of existing careers, but rather emanates from within, emerging organically through following what genuinely energizes you? While our achievement culture celebrates those who persist in singular domains, we need more stories of people who dared to walk away from one game to play the next, without knowing their potential in the new realm.

The most exciting opportunities of tomorrow exist in the spaces between established fields, in the synthesis of seemingly unrelated domains. Previous experiences are never wasted—they integrate into who we are in ways we can't predict.

The path forward has already been paved. The greatest freedom comes from pursuing what deeply interests us and trusting that our experiences will weave together in unexpected ways. I invite you to embrace being hard to describe3—after all, the future belongs not to those who fit neatly into existing categories, but to those who dare to transcend them when their inner compass points in new directions.

Here’s the source. Separately, I heard that Google laid off a bunch of Python engineers because it turns out AI can write Python, a relatively simple programming language, really well, but I couldn’t find concrete evidence so I refrained from mentioning that.

My old friend Albert AKA BoxBox has over 1.3M subscribers on YouTube currently. Learn more about him here.

Another way of saying this is having high self-complexity

Love this term, thank you for the in depth explainer, which made me feel very seen xoxo

Love this, and hope all your readers are taking you up on the invitation to evolve! And thank you for the framing around the Integrator's path, that really resonates. I would submit that a secondary, if not the primary, challenge for Integrator's is how to articulate their "value proposition" to the market. Not everyone can be like John von Neumann, who was paid by the RAND Corporation for the thoughts and ideas that came to him while shaving :-)