#17: Revisiting Gratitude vs. Ambition

the tides are turning

It’s Saturday morning and I’m sitting in Maker, a local coffee shop in the CBD (Central Business District) of Melbourne. Prior to arriving in Australia, I had done zero research and the extent of my Australian knowledge was that I like smashed avo (avocado toast), Rufus Du Sol, Tash Sultana, and Crooked Colours. The chill culture that I’ve observed indirectly through Youtube and from trying to schedule a meeting with my Aussie colleagues, but then seeing their calendar blocked out for six weeks of ‘Annual Leave’ was intriguing to me. I came here open-minded to see firsthand the similarities and differences. It’s my first international trip since Feb 2020 when I went to Seattle → London → Bangalore → Taipei as part of my Uber work trip. I remember walking around downtown Taipei seeing everyone wearing masks, getting our temperature checked at every building we entered and thinking life in America was going to remain unchanged. How naive of me.

Hey everyone 👋 Feel free to reply and leave a comment and if you’re not already subscribed, you sign up for free to receive new posts:

The past few days of traveling alone have been incredibly refreshing. I’ve finally been able to sit (both literally and metaphorically) and process things. It wasn’t until this week, in retrospect, that I realized that I overextended myself during the past few weeks. I guess that should be expected when you try to travel full-time while working full-time. Starting in late July, I spent five weeks driving up to Washington from the Bay Area. Then I headed east to Glacier in Montana and then Jackson Hole in Wyoming. When I was first planning this road trip out loosely when I was still living in Hawaii, I suspected that it would push me to my limits in terms of trying to do too much. They say hindsight is 20/20 and present me is here to report that I was right - I did bite off more than I can chew. In terms of just pure hours, I was trying to do a lot with juggling big multi-day backpacking trips and work. It was hard to fit everything I wanted to in a day when I had to figure out things that I otherwise wouldn’t have to think about in normal life. Things like where was I going to get wifi to work, where was I going to get food because I didn’t have a kitchen or even a cooler to keep food in, and where was I going to sleep that night.

The road trip is actually not the full extent of how I ended up doing too much. Originally, I had planned to spend the following week at home to unpack, enjoy some home-cooked meals with my family, and finally sleep on a real bed, but life had other plans. I flew out to NYC the day after I got back from Jackson Hole and then spend a week in NYC, sleeping on couches, air mattresses, and luckily a real bed (when a friend’s housemate was out of town). I came back home and then two days later I was on another flight from San Francisco to Honolulu. Recently, whenever I’ve making plans, I haven’t thought to myself whether it would be too packed or too much in such a short period of time. I’ve skipped over that questioning because up until recently I haven’t had an issue with traveling so much with not a lot of time to rest in between. Now that I’ve had a few days to myself in Melbourne and sleeping in an actual bed, I’ve been able to notice some things that I was just too busy, too scramble-minded to pick up on.

Lately, my ambition has been at an all-time high, but it’s in the traditional, default sense of professional career. It wasn’t until I was back in Hawaii last week that I noticed how much my mindset has changed in the last three months. Being back in the ʻāina brought my recent memories of living in Hawaii to the foreground. I was reminded of my days of yoga, surfing, coffee shops, and cooking for friends. Every time I’m back in Hawaii, I end up being more introspective about things like my health, goals, future, purpose, and other deep life topics. Maybe it’s the palm trees, ocean waves, comfortable humid air, the pace of life, the people or everything combined. I ended up questioning whether my newfound, increased ambition was even a good thing because I realized that with the greater ambition, came a decreased sense of gratitude. In the last few months of figuring out where I’m headed next (in all senses), figuring out my goals and restoring my level of ambition, my sense of gratitude receded gradually without me noticing. As ambition increases, gratitude degrades slowly, slow enough that it’s hard to notice it changing - like the opposite of [boiling frog syndrome](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boiling_frog#:~:text=The term "boiling frog syndrome,severity until reaching catastrophic proportions.).

Last week, I became aware of what I used to take for granted. When I was living in Hawaii earlier this year, I wouldn’t be stoked to surf unless the waves were 4ft or bigger. I wouldn’t even think about surfing at Canoes unless a friend was visiting and staying in Waikiki without transportation. On this quick visit, I started smiling wide like a little kid as soon as I stepped into the water at Waikiki Beach with my giant log of a surfboard that I rented from Moku. On my last day, I surfed at my favorite south shore break Marinelands in Ala Moana with Grant and Kora. In a bittersweet way, it feels strangely comforting to know exactly what I’m walking away from in this transition to my next chapter. I’ve experienced how amazing it is to live in Hawaii, but I also know that it’s time to experience something else. It’s comforting in an unorthodox meaning of the word because I know that I won’t have fleeting thoughts of an imaginative picturesque lifestyle while I’m on the grind. I know exactly what it feels like through my lived experiences and I plan on returning to it at some point - just not right now.

Let’s link and build?

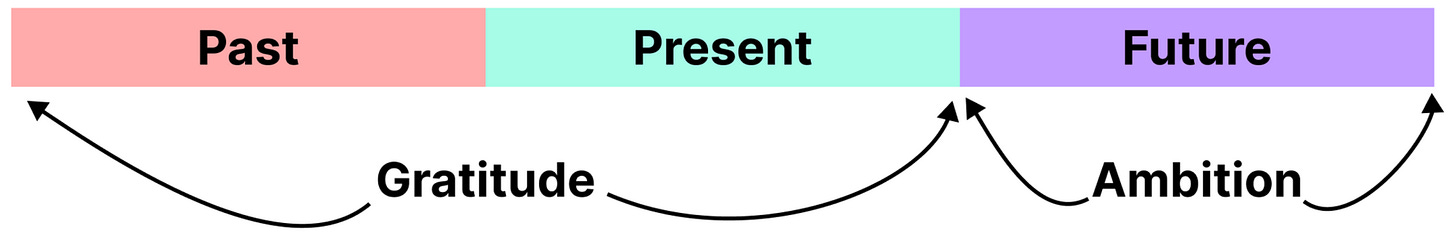

In #10: Gratitude vs. Ambition, I explained why I think gratitude and ambition often feel like two opposite ends of tug-of-war in an infinite game of push and pull. I tried to sum it up with being grateful for the past and present and staying ambitious about the future:

I included this 2x2 chart of different personas with Ambition and Gratitude as the respective X and Y axes:

I was thinking about this topic recently when I was talking about it with my friends JV and Victoria in Hawaii and without re-opening the newsletter, I was trying to remember what I placed in the upper right hand quadrant - the ideal state of high ambition and high gratitude. My memory failed me as I thought there was actually a persona that I thought of, but looking back, I think it’s empty because at that time, I didn’t know what to actually put there. I didn’t what it actually looks like to radiate ambition and gratitude in a balanced manner. I still don’t know, but at least I have a better sense after the past couple months.

Dr. Gena Gorlin is a psychologist who focuses on motivation and self-change. In The Builder's Mindset, she introduces the concepts of a zen master and a drill sergeant. Rather than viewing it as a dichotomy of ambition vs. gratitude, she looks at it from the lens of inputs vs. outputs. The zen master only concerns themselves with the inputs because “it’s about the journey, not the destination” and “Don’t worry about the outcome, just focus on the process.” The problem with this is “that they sell themselves short, either giving up too easily or setting unambitious goals in the 1st place—all for the sake of minimizing stress. In muting the abusive voice of the “drill sergeant," they also mute their desire, their passion, their will to find a way. They settle for “ok” jobs and “ok” relationships, foregoing the stressful turbulence and risk of failure that more ambitious moonshots would bring.” On the other end of the gradient is the drill sergeant, which focuses on outcomes over process. If you take it too far, then you end up beating yourself up and burning out.

Just as I realized that positioning ambition and gratitude as two opposing forces is a false dichotomy in post #10, Dr. Gorlin realizes the same for process vs. outcomes:

As with many false dichotomies, the intuitive assumption may be that the drill sergeant and the Zen master are opposite ends of a single continuum, and that therefore we’d do best to take the middle road between them. But I submit that these two mindsets are more similar than different in their fundamental assumptions about the nature of human goal-pursuits. In particular, both are ill-suited to the work of building. What’s needed instead is a radically new mindset; one befitting the distinct relationship between a builder and that which they work to build.

Both the drill sergeant and the Zen master ask us to separate ourselves—our needs, our desires, our day-to-day experience of our work within the larger context of our lives—from the outcomes we aim to achieve. The drill sergeant says: ignore yourself. The Zen master says: ignore the outcomes. But that’s like separating one’s choice of building site and materials from the type of building one aims to build.

A builder chooses what she wants to build, and she holds herself accountable for the work of building it. She is not beholden to any inner or outer drill sergeant; only to her own independent, carefully formed judgment of what is worth building and how best to go about it. And she neither beats herself up nor lets herself off the hook when something unexpectedly cracks or falls out of place; rather she problem-solves like mad until she finds a solution.

I like the framing of a builder as someone who cares about the process and the outcomes. It’s important to care about results, but also not fixate on results because so many things are outside our control. I also like the builder (or craftsman) analogy because they are internally motivated to keep progressing rather than look for external validation. In reading The Builder’s Mindset, I visualize the potter sitting at the wheel by themselves or the athlete training alone or the writer hunched over scribbling away. In each of these scenarios, the person is focused on their craft and cares just as much about the process as the outcome.

The process of building—of creating something new and valuable—is a constant progression of choices. Each choice is connected to and made meaningful by some envisioned outcome, which itself is a choice made in the context of other envisioned outcomes, such as building a career in which one gets to solve interesting design challenges all the time.

Building is fundamentally self-expressive, invigorating work. A builder does not waste time on tasks she does not judge to be constructive, nor does she begrudge even the most menial or unglamorous tasks when she knows they will get her closer to her envisioned masterpiece. Contrast this to the kind of white-knuckling and self-shaming by which so many people force themselves (drill sergeant-style) through the series of uninspiring chores they call “work.”

And building is ambitious, goal-directed work; builders care deeply about the quality of what they are building, and hold themselves accountable even for the problems they don’t yet know how to solve. If they no longer see value in what they are building, they wrap up their prior commitments and then move on to something else.

Ambitious in a different way

At first, with sensing that I was becoming more ambitious, I was concerned that all the non-career aspects of my life would become a lower priority and degrade. To some extent, if you focus on one thing, that implies less time is available to spend on extracurriculars. Traditional teachings on what it takes to be excellent in any field suggest that you have to sacrifice everything else - including your health, relationships, hobbies, etc. In going from broad exploration to narrow focus, I will (and have already) made certain sacrifices so I’m not dismissing this notion. However, I am challenging myself to stay in balance as much as I can. To not be comfortable with losing the progress I’ve made in improving my health or fostering relationships. In that sense, I think I’m actually quite ambitious because it’s actually really hard to accomplish what I’m striving for. It’s rare to see someone achieve excellence in something (sports, entrepreneurship, arts, etc) AND also stay healthy, grounded, happy, sane through it all.

Steve Schlafman, a former VC-turned coach, says in Lightwaves #005: Ambition Shifts:

I absolutely want to be great at what I do and live a healthy, balanced and good life. They are not mutually exclusive.

This isn’t a groundbreaking statement and shouldn’t be controversial at all, but for some reason when I read this a week ago, I paused. We celebrate entrepreneurs like Elon Musk, Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos, but between the three of them, they’ve had six divorces total.

I think my greatest ambition is to prove to myself that I can be successful without sacrificing my happiness. That I can live in balance and be an ambitious person trying to improve the world while also taking care of their home. “Their home” representing myself and my mind. It should be a prerequisite to have your house in order before trying to do something bigger than yourself. It’s the equivalent of airlines telling you to put the oxygen mask on yourself before helping others. Like you can’t try to do cool external shit if you can’t even calm your mind down or stop thinking negative feelings.

A few more quotes:

For a long time I thought I wasn’t ambitious, until I realized my ambition is to live a good life.

Oscar Wilde:

Our ambition should be to rule ourselves, the true kingdom for each one of us; and true progress is to know more, and be more, and to do more.

Ambition is understood by most people today as trying very hard at something career-related. If you’re an ambitious software engineer, then you try to write really good code. If you’re an ambitious basketball player, then you want to make it to the league. If you’re a baker, then you want your muffins to taste heavenly. This narrow definition of ambition excludes the possibility of being ambitious in multiple pursuits or being in balance. We don’t associate being ambitious with non-intense things, but I would like to think I am just as ambitious about being as zen as a yogi as I am ambitious about creating a successful career in tech. It sounds weird to be ambitious towards being chill; the very thought of “trying hard to chill’ reads like a contradictory statement.

Another way I think about it is in terms of maximums and minimums. I am trying to maximize my career while setting high minimum thresholds for my physical health, mental health, relationships, etc. My generation gets critiqued by boomers for being soft and not knowing how to work hard. While not all of the criticism is fair, some of it is true. During peak COVID, when the federal government was handing out an extra $600 per week in unemployment benefits, I know someone my age who didn’t bother trying to find a job and instead took that “free” money to buy a $1000 drone and chill at home with his parents. I was kind of pissed to. hear that because although I was also getting the same stimmy checks, I was stressed out looking for a job ASAP.

So yeah, in the next chapter I am trying to work hard, but I’m also trying to be ambitious about living a healthy, balanced life. That’s where the minimums come in. By putting up guardrails for exercise, quality time with friends, eating right, sleeping enough and more, I’ll be able to strive for maximum performance in my work (caveat: work ≠ job) without burning out.

No regrets Ragrets

I hit my limit this past month when I did a five week road trip immediately followed by a week in NYC and then a week in Hawaii. I guess it checks out to feel tired when you spend a bunch of time not sleeping on a real bed and take red eye flights across the country. But I don’t have any regrets about packing my schedule like this. If anything, I’m glad I did it this way so now I know what my limit is. I’ve been thinking about the concept of “finding my limit” recently. I think most people, including myself, don’t know what their limits are. You might think you have a limit like thinking you can only run 4 miles before collapsing, but then you run 4.1 miles and realize you could keep going. So the limit is like a fog cloud that you approach and then once you get there you can just go past it instead of hitting a wall or falling off a metaphorical cliff.

Limits exist in multiple formats. I hit my surf limit when I paddled out into 10-12 feet waves at 6:30am on an eerie morning. There was only one other person out there and I couldn’t even duck dive because I had a 8’ board. I got pounded by a couple waves in a row and then picked up two broken boards on my way back in. Spooky times! I hit my ski limit when I dropped into Corbet’s Colouir at Jackson Hole last winter. The hard packed snow made it incredibly easy to catch an edge on the steep drop in and I fell over halfway down the run. Fortunately I didn’t hit the massive boulder in the middle of the run as I tumbled down like a rag-doll and because my skis dislodged at the very top of the run, I was able to hike all the way back up and at least claim I skied most of the run.

I think it’s important to figure out what your limit is (work, sport, art, anything) because if you don’t, then you’re leaving a lot on the table and will never reach your full potential.