#8: The Stories We Tell Ourselves

how we shape the past to make sense of the present and the future

A Story about a magical sunset in Grand Canyon

During spring break of sophomore year, I embarked on a nine day road trip with 15 friends that started in Berkeley and weaved through Joshua Tree, Grand Canyon, Antelope Canyon, and Zion. It was my first road trip outside of the east coast and I had never been to Utah or Arizona. We were all broke college students so we tried to save money by camping and making meals out of Costco groceries. For every single day, I ate the same two meals over and over, one was savory, the other was sweet. Meal #1 was canned chicken breast with barbecue sauce on pita bread. Meal #2 was banana, peanut butter, and honey on pita bread. I ate Meal #1 and Meal #2 multiple times per day. I won’t say which one I enjoyed more, but let’s just say I haven’t had canned chicken ever since.

I was reflecting on this trip since my friend David who was on this trip was in Honolulu this week with his family for vacation. At one point during our sunset walk at Ala Moana beach which transitioned into dinner at a Szechuan restaurant, the road trip came up as a past memory. I was mid-sentence in recalling the last sunset we saw at Grand Canyon National Park. It was just below the rim and we were perched on a rock shelf that seemed to jut out into the sheer openness. Getting to the spot that we settled down at was difficult. We first spotted it when we looked down from the viewpoint on the rim trail and it seemed like the perfect place to catch the sunset with no trees or large rocks to obstruct the view.

David interjected to finish my sentence as I was about to describe how epic the sunset was. According to David, when we were at the rim looking down in search of a sunset view, there were already people down there. He said he was glad we all made it down and explained how it was a metaphor because if you see others achieve something amazing (like making it down an unmarked path to a dope viewpoint), rather than think it’s not possible for ourselves, we should think “If they can do it, why can’t I?”

I have an entirely different account of the memory. When I play it back in my head, we were at the top of the canyon and when we scanned below to scout for a quiet sunset viewpoint, we looked down and saw no one. I remember evaluating if the lower rock shelf was even possible to get to since there was no evidence that it was connected to the trail that we were on. And after wandering around the area in search of any sign, we spotted what looked like a steep decline of rocks that vaguely had signs of past hikers traversing down. In my head, even as we were already making our way down the mountain, it still wasn’t certain that we were headed the right way and wouldn’t encounter any obstacles.

In David’s version of the story, we’re pushing through and navigating the rocky path down because we know that it’s been done and that we’re capable of doing the same. In my version, we’re in explorer mode, wondering if it’s even possible. Regardless of what actually happened that evening, I find it fascinating that we remember two different versions of the story and that it was memorable for both of us.

This led me to wonder how much of what we remember as fact has been manipulated by our minds in an effort to explain our own journey from past to present. Today, David knows his career trajectory and has ambitious plans to achieve greatness. On the other hand, I’m less sure of my career path and although I would say I’m also ambitious, it sometimes doesn’t feel appropriate to use that word when I don’t even know what singular pursuit would receive my ambition. My current state resembles how I felt at Grand Canyon - adventurous, unsure, curious. This moment was just a five minute blurb within a five hour catch-up, but it’s been on my mind since and made me think about a concept I guess we can call The Stories That We Tell Ourselves.

Why we tell ourselves Stories

As humans we have a fundamental need to understand the world, our surroundings, and ourselves. We have a psychological need to feel like we’re in control and we also have a bias towards optimism. When things don’t make sense or are unknown, we feel out of control which subsequently leads to us scrambling to put the puzzle pieces together. Out of all the things that need to make sense, it’s our personal journey that is most important for us to understand. Since without a narrative with a fable-like beginning, middle, and end, we would feel like we don’t even have control of the most important thing - ourselves.

It’s evident that we construct stories about our personal history whenever we’re asked “Tell me about yourself.” Whether it’s a podcast, interview, or coffee chat, whenever someone is asked this question, they start from the current frame of who they are. There’s an internal audit that self-examines in this moment what they look like, what are they doing, and how are they feeling. Then the mind wanders in retrospect, attempting to weave together past events in some sort of hacked together chronological order where one event leads to another in a logical manner. We’ve all seen this before when we say “I grew up in X, then I studied ___ at Y University. I was interested in ____ so I became a ____ and that’s how I got here.” We want to believe that everything happens for a reason and that we’re in this moment we are doing exactly what we should be. Because if we’re not doing what we should be, then that leads to a big problem - AKA the existential crisis or midlife crisis that people often experience.

Constructing our Life Timeline

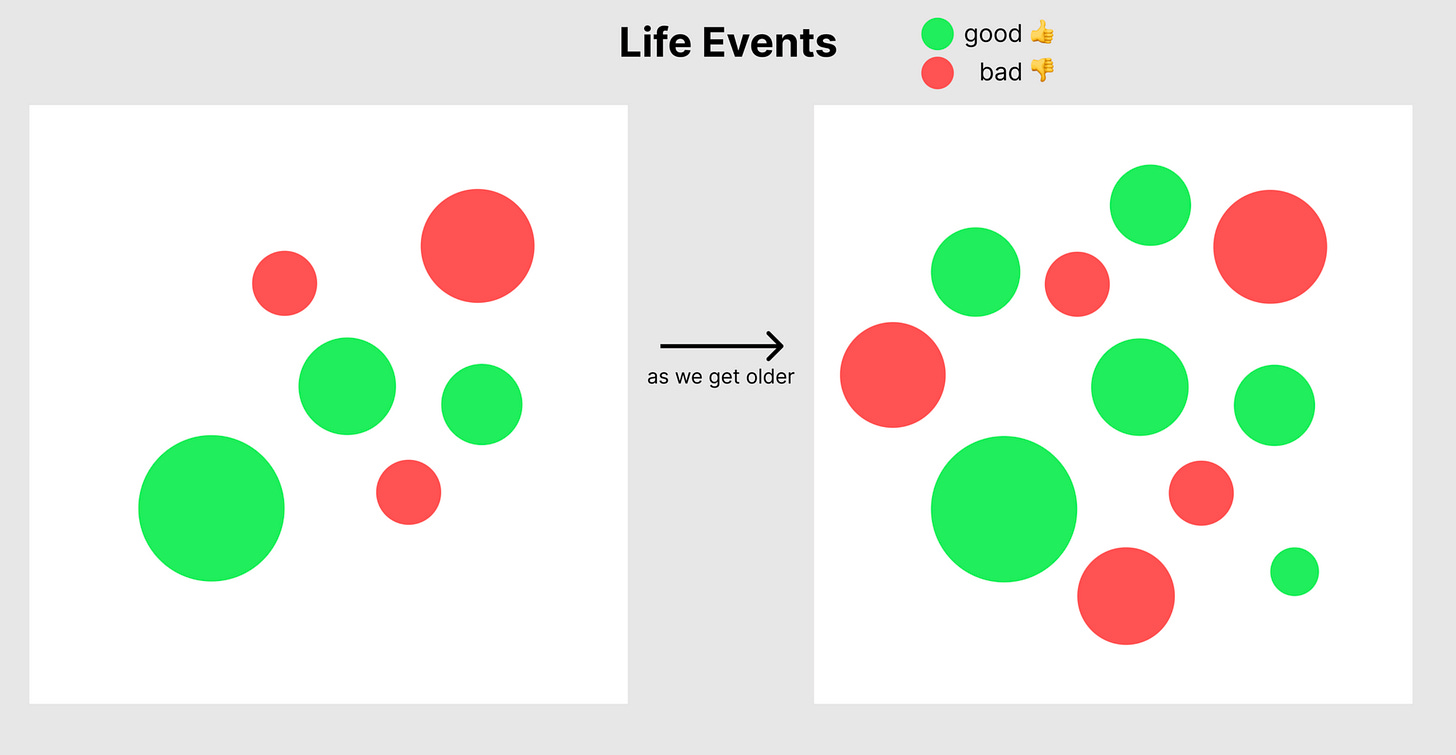

As life goes on, we collect Life Events that get recorded in the form of memories. For simplicity’s sake, each of these Life Events is generally positive or negative and has an associated magnitude or size of impact. Green bubbles represent positive events and could range from tasting a freshly baked chocolate chip cookie which would be positive, but smaller in magnitude than the first time traveling internationally. Red bubbles are negative events that were particularly memorable or important in our development such as breaking a bone, getting laid off, or losing a loved one. Over the years we collect these Life Events and they sorta just float in our minds and are undisturbed most of the time.

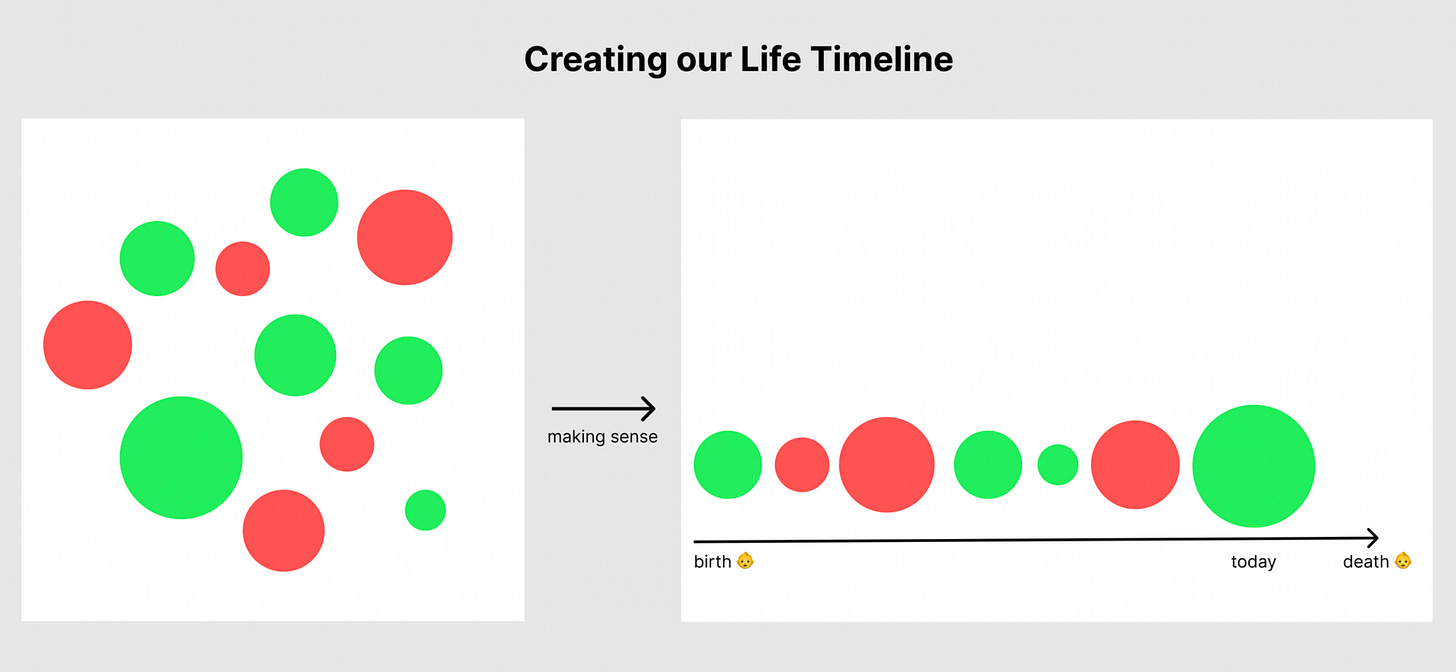

At some point, we’re prompted to tap into our library of memories and examine them. It could be when we’re asked in an interview “so… tell me about yourself” or when you meet someone from the first time and they ask “oh how’d you end up doing ____ for work?” Or maybe when we’re sitting on a long international flight staring out the window wondering what is the meaning of life. That’s when we start to weave together our Life Events into a timeline that makes sense to us.

As we reflect on the past, there are certain Life Events that we choose to include, but also some that don’t make the cut. We tell ourselves that it has to be a mix of green and red bubbles because life is never all good or all bad. The end result is an attempt to create a coherent, well-crafted story that makes sense to both ourself (the author) and others. However, we’re constantly undoing and weaving the timeline back together as we collect more memories and update the library of Life Events. Depending on who our audience is (self vs. interviewer vs. new friend), we might even tell a different version of the story. The moments that we hand-pick to include in our Life Timeline and inversely, the ones that we deliberately exclude serve us to justify our past and explain the present.

The Hero’s Journey

For any situation, there’s always a way to tell a story that results in people nodding their heads in comprehension. There’s a plethora of idioms, phrases, and parables and each time we need an explanation we can just reach into this grab bag and pull out the one that fits the best. If it takes someone a long time to achieve their goal, then we say “good things come to those who wait”. But if a rare opportunity pops up and we spontaneously decide to take it, then we say things like “the early bird gets the worm” or “don’t wait, seize the moment”. There’s a reason why society loves a good underdog story, but that also can lead to us constructing David vs. Goliath narratives and of course, we’re end up assigning ourself the role of David. The tendency to make sense of everything results in the usage of Reality Goggles to construct the Hero’s Journey for ourselves (emphasis mine):

We are betrayed by our maps of salience [Reality Tunnels" or "Reality Goggles"]. They plot our narratives, identify our enemies and then coat them in distorting layer of loathing and dread. We feel that hunch withdraw and then conduct a post factum search for evidence that justifies it. We are motivated to fight our foes because we are emotional about them, but emotion is the territorial scent-mark of irrationality. We tell ourselves a story, we cast the monster and then become vulnerable to our own delusional narrative of heroism. The Demon-Maker loves this kind of binary thinking. It insists upon extremes: heroes and villains, black and white, in-tribes and out. … The Hero-Maker exposes this strange urge that so many humans have, to force their views aggressively on others. We must make them see things as we do. They must agree, we will make them agree. There is no word for it, as far as I know. ’Evangelism' doesn't do it: it fails to acknowledge its essential violence. We are neural imperialists, seeking to colonise the worlds of others, installing our own private culture of beliefs into their minds. I wonder if this response is triggered when we pick up the infuriating sense that an opponent believes that they are the hero, and not us. The provocation! The personal outrage! The underlying dread, the disturbance in reality…

I will try to remember, though, that as right as I can sometimes feel, there is always the chance that I am wrong. And that happiness lies in humility: in forgiving others, and in forgiving myself. We are creatures of illusion. We are made out of stories. From the heretics to the Skeptics, we are all lost in our own neural tjukurpas, our own secret worlds. We are just ordinary heroes fighting phantom Goliaths, doing our best in the service of truth when the only thing that we really know are the pulses.

- Storr, Will. The Unpersuadables: Adventures with the Enemies of Science

To each of us, we are the Hero, forged from an incomplete, leaky library of memories and selectively woven into a story in the form of a Life Timeline. We choose what to remember based on what will make the most sense for our present self and for our future goals.

Some Stories I’ve told myself

Caffeine

Admittedly, I am a daily coffee drinker and I’ve become used to structuring the hardest mental (or physical) tasks for when I’m caffeinated. I recently caught myself telling myself that I can’t read, write, or do anything particularly challenging unless I’ve got a cup of joe next to me. It’s definitely easier to lift weights or voraciously consume a book when the coffee is flowing through me, but I think I’m over-exaggerating the effect and need to work on becoming less dependent on caffeine (although my one cup / day habit isn’t that unhealthy, IMO).

Sleep

In a similar way, as a byproduct of learning the important of getting enough sleep, I told myself that the inverse is the absolute truth - if I don’t get enough sleep, then I’m operating deficiently and the whole day is wasted. I proved myself wrong this week when I still made it to the gym after only getting five hours of sleep the night before and the weights didn’t feel as heavy as I thought they would. It’s true that sleep matters, but it doesn’t serve me to think the day is wasted if I got less sleep than usual.

Do outdoor sports enthusiasts make for better businessmen/women?

I read this tweet below a few weeks ago and found myself eagerly agreeing. Well, of course I would - I like skiing and surfing and would also like to be successful in business one day. There’s no proof that this is true and there’s a clear correlation between privilege, money, pre-existing success with expensive sports like skiing and surfing. It’s also hilarious because when revisiting this tweet, I realized in the thread it’s revealed that this dude skis and surfs.

The books we choose to read

A couple years ago, I decided to read Range by David Epstein. It’s actually ‘the why’ I decided to read it that’s more interesting than the contents of the book. I remember picking it up and reading the flaps of the hardcover sleeve to get a glimpse into the book and deciding to read it because it asserts that being a generalist is more effective at achieving success than being a specialist. I think I chose to read this book because I already knew at the time that I am more of a generalist than a specialist.

If we only read or consume content that confirms our existing beliefs, then we’ll end up avoiding new or opposing ideas. In the case of me reading Range, I think the harm is relatively minimal, but apply this to more people and for other forms of content and you arrive at the current situation with Fox News vs. CNN/MSNBC. If you watch Fox News, then you won’t believe anything you see on CNN and vice versa.

What can we do about it?

I don’t have it all figured out and I’m not even sure if this is entirely avoidable. With that disclaimer said, I think there are a couple tools that can be useful:

Try new things

We tell ourselves stories about our past to explain how we got here and validate our goals for the future. By trying new things, we get ahead of the stories we tell ourselves by deviating from what’s already been done before. Being exposed to unfamiliar territory scrambles the metaphorical radio frequency of trying to form a coherent Life Timeline because it becomes harder to form. Trying new things puts us into proactive mode of shaping our path rather than staying in reactive mode to tell stories. (Trying New Things pt.1 | Trying New Things pt.2)

Reading books that have endured the test of time

Rather than constantly read books that strengthen my existing beliefs, I want to read more on ideas that are new or against what I currently believe. There are classics that have been read by generations and critiqued endlessly. If decades have gone by and they’re still considered great, then it’s probably worth checking out at the very least. This is an example of The Lindy Effect.

Journaling

By capturing my thought process in the moment and then not allowing myself to make any edits later on, I’m able to document my decision making and how it evolves over time. I’ve been thinking about one particular decision for months now and I keep changing my mind. Whenever I change my mind, I write down my thoughts and it’s helpful to look back and see what I was thinking.

Wow this is such a great read and it's great to see we have made similar observations. These two lines stood out perfectly to me:

"To each of us, we are the Hero, forged from an incomplete, leaky library of memories and selectively woven into a story in the form of a Life Timeline"

"This led me to wonder how much of what we remember as fact has been manipulated by our minds in an effort to explain our own journey from past to present. "

Everyone thinks they're a hero from their perspective, and yet they became a hero from self-selecting stories that fit the narrative they want. It's the game we all play haha