#29: Finding Flow ☯️

balancing awareness and attention

Recently, it’s come to my attention that all the ski-related injuries I’ve accumulated over the years have occurred when I wasn’t paying attention. In 2020, while traversing across a relatively flat ridge, I mistakenly skied across rocks veiled by an inch of snow, slamming my left patellar tendon against a jagged boulder. Earlier this year, I was in Jackson Hole on my sixth consecutive day of powder skiing and my legs were so exhausted that I fell and sprained my right thumb by smashing it with my right knee. A couple weeks later, I was in Park City on a mellow blue groomer when the terrain suddenly changed from smooth and illuminated by sunlight to choppy and shaded. I must’ve clipped a rogue mogul because I popped out of both skis and launched forward about twenty feet. After a quick adrenaline-induced self-examination and realizing I was fine besides a 3/10 pain in my rib whenever I exhaled, I just sat there wondering why this crash even happened.

A week ago, I was back again at Kirkwood ski resort, the place that once claimed my left knee. It had snowed 17” in the past 24 hours, which is what every skier prays for before they go to sleep every night. On my third run, I had already skied the steep off-piste section of the mountain. I shot into a gulley known as The Drain and started fidgeting with my action camera that was strapped to my chest. I wasn’t looking carefully at what was in front of me, but I wasn’t worried because the terrain wasn’t steep and I knew peripherally there wasn’t anyone around me. As I rounded left around the corner, my wide and especially light skis clipped a newly formed mound of snow and I fell forward out of both skis landing on my left shoulder. At first, I was in so much pain that I couldn’t move my shoulder and thought it was dislocated or broken. As I sat in the snow accompanied by a kind skier who stopped to help, a million thoughts raced in my head, but I kept fixating on the fact that about an hour earlier, I got a text from my mom saying I got denied by the state-run healthcare. I alternated between feeling the physical pain in my left shoulder and the potential pain to my bank account if I had to pay out-of-pocket for treatment. The good news is that my injury is just a bad sprain or minor rotator cuff tear rather than something more serious and it turns out the healthcare rejection was a mistake - I’ve had coverage this entire time. Over the last week, as I consumed copious amounts of collagen powder, oxtail stew, and bone broth in an attempt to recover as fast as possible, I reflected on why all of my ski injuries have embarrassingly occurred in relatively mellow settings rather than the actually dangerous no-fall zones (if you fall, you fall all the way down) I’ve skied without a single scratch (knock on wood).

Flow States

Positive psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi coined the term “flow state”, the feeling of being fully immersed in whatever you’re doing. It’s the deepest, most intense form of attention. When time slows down and you know exactly what you want to do from one moment to the next. In the flow state, you’re fully concentrated on the present moment with no mind space for the past or the future. It’s a state of being that brings substantial meaning and fulfillment such that “asking how often people get into the flow state is a good predictor of their sense of well-being”. Fortunately, cultivating flow is a skill that can be trained and is highly contextual to the individual. I’m grateful to have discovered activities that bring me to a state of deep immersion like skiing, surfing, hiking, and writing.

Time isn’t linear. It exists on a dynamic range. Waiting in line at the DMV or filing taxes on TurboTax can make an hour feel like an eternity. But in flow, time passes in the blink of an eye. Last year at Aspen Snowmass, the snow gods blessed us with twelve inches overnight with another foot of pow throughout the day. I took the slogan “no friends on a powder day” quite literally and opted to ski alone. It was mid-week and without any weekend warriors clogging up the runs, we had the entire resort to ourselves. I remember wolfing down my turkey wrap that I stuffed in my pocket while riding a chairlift solo. It was still dumping as I re-fueled. Like a giant Salt Bae was in the skies above us sprinkling snowflakes so large you could see their individual shape. I took only one break to pee and get a few sips of water. Maybe dehydration doesn’t exist when in flow. Strava tells me that I skied for 6 hours and 13 minutes, but it felt like a single moment.

Expanding Awareness

Being in flow state is described as the optimal state of consciousness and even its termer Csikszentmihalyi says “once it becomes intense, leads to a sense of ecstasy, a sense of clarity”. However, that doesn’t mean always being in flow state is ideal. When we’re in the deepest form of attention, we’re fully immersed and inversely our sense of awareness shrinks. One time I was writing and lost track of time so badly that I was late for coffee with friends by two hours. My tardiness exceeded the blame-it-on-traffic excuse threshold, but I had trouble convincing them that I was genuinely so deeply focused that I forgot when to stop. The state of being “in the zone” is blissful, but there are times when we should regain our awareness.

In The Creative Act, Rick Rubin explains “regardless of how much we’re paying attention, the information we seek is out there. If we’re aware, we get to tune in to more of it. If we’re less aware, we miss it.” While statements like this might seem hand-wavy, I have found a lot of truth in slowing down and expanding my awareness. If employing maximum attention is to be in flow, then what does it mean to be in a state of maximum awareness?

Being in a state of expanded awareness nourishes our creative muscles and enables us to notice new opportunities. Most of my creative insights surface unexpectedly during seemingly mundane moments. It could be while showering, driving, or taking a walk. I’ve said before that I’ve had insights pop into my head while sitting in the gym’s steam room that I’ll speed walk past the showers to my locker just to pull out my phone and note down the thought before coming back to shower. To quote Rubin once more: “It appears in a moment. An immaculate conception. A divine flash of light. An idea that would otherwise require labor to unfold suddenly blooms in a single inhalation.” While he doesn’t go into the optimal environment for inspiration to strike, I’ve observed that inspiration is more likely to strike when we’re in a state of maximum awareness and openness.

Until I read Stolen Focus by Johann Hari, I couldn’t explain my newfound sense of creativity. I mean, all I did was quit my job. Where were all these new ideas coming from? Hari explains that creativity comes from your brain forming new connections beneath the level of your conscious mind. “Your mind given free undistracted time, will automatically think back over everything it absorbed, and it will start to draw links between them in new ways.” These creative insights only catalyze during brief periods of slack when the mind has a chance to catch its breath. Doing the opposite i.e. multitasking results in the “creativity drain” because the mind is too busy context switching and error-correcting to form new neural pathways. With the benefit of hindsight, I suspect that most of my time spent working as a product manager was in multitasking mode. It’s not that I surged in creativity upon quitting, I was suppressing this essence that always existed within me.

Growing up, my favorite shirt from Coach Wootten’s basketball camp had this Seneca quote on the back, “Luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity.” After reading about society’s collective depleted awareness resources in Stolen Focus, I’d amend the phrase to “Luck is when preparation meets opportunity and awareness”. Maybe back in Ancient Rome the extra bit wasn’t necessary, but today everyone is nearly a cyborg with Airpods always in and smartphone within arm’s reach at all times. Opportunities are boundless and serendipity is inevitable, but only if you actually spot it. Our perception of reality bends based on how aware we are of other people, our environment, and of course, ourselves.

Balancing Attention and Awareness

If flow state is when we’re at peak attention and maximum awareness generates creativity and opportunities, then how do we reconcile the two? It’s impossible to be simultaneously completely focused and aware of everything around you. So when should we dial in to find flow and when should we open ourselves up? To answer that, I look to two examples: design principles and the creative process.

The double diamond framework of how to go from problem to solution is taught in every Design 101 class. It can actually be broken down into two phases of awareness and two phases of attention.

As the designer, you discover the customer’s problems through interviews, surveys, and analytics. From there, you hone in on a specific problem, the one that’s most important to solve for, at this moment. The first diamond is all about picking the right problem. The second diamond starts with an open exploration into a variety of solutions and through focused iterations of testing and feedback, you get to the solution.

The creative process follows a similar diamond form that flexes between exploring and exploiting. The best writers read a lot. The best filmmakers watch tons of movies. There are no new ideas, only new forms of synthesis and packaging. I like to think that every artist lives in a cave. They’d prefer to stay cozy in the cave creating, but need to periodically venture out to gather firewood or forage for food in order to survive. The creative process is an endless interweaving of gathering ideas outside and then sheltering inside to create. Without any creative fuel (inspiration), you can’t create. Without returning to the cave (or studio), you lack the tools and space to create.

If you’re feeling malnourished in ideas, then maybe you should go find some. They’re everywhere:

Being open to receiving creative inspiration and opportunities is just as vital as the effortless presence found in flow. Recognizing these complementary powers need to be balanced like yin and yang, I strive to flow between maximum attention and maximum awareness.

P.S.

I’ve skied in quite a few places now and sometimes a friend asks me, “What’s your favorite place to ski?” I respond by saying that it’s not so much dependent on the ski resort as much as it’s about the specific days. Days like skiing triple blacks at Big Sky and celebrating with pocket chicken wings. Flopping into Corbet’s Couloir like a dead fish and then having to hike all the way back up for my skis. My entrance gets 0 stars, but I still skied it. Skiing 35K feet of vert solo at Breck on my 5th consecutive day of skiing (Whale’s Tale is GOATed). The annual pilgrimage to Crested Butte. The list goes on. At first I thought these were my most memorable days of skiing because that’s when the snow was the best. Or maybe it was the company. Now I realize that these are the days when I was completely in flow state. For those moments, all I could think about was connecting one turn to the next.

P.P.S.

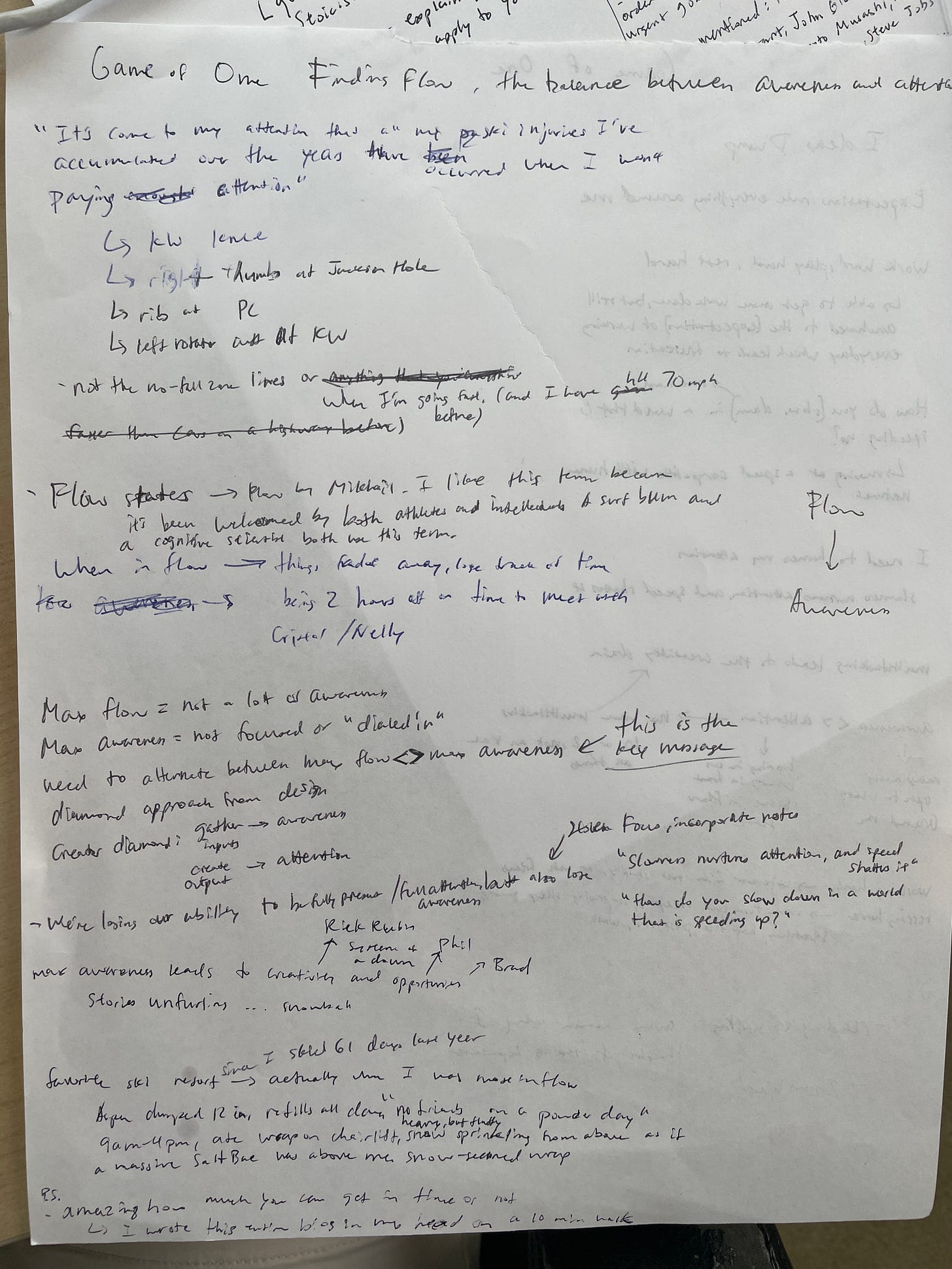

This entire blog wrote itself earlier today on my morning walk. From the opening sentence to the last thought that I haven’t even typed out yet, it was all in my head. I got back to my desk and scribbled down everything hastily in fear of forgetting anything. That’s why it looks like chicken scratch. Chicken scratch that came from awareness.

Loved all parts of this post! You’re especially on the money when explaining how creativity flows into us when we’re undistracted and open. I find that many of my most important revelations come from plane rides with no wiring as I have 2-5 hours of uninterrupted focus to explore my own mind!

So neat to see your chicken scratch notes at the bottom. I definitely want to experiment with writing like that :)