#13: Mt. Shasta & Tolerating Discomfort

how increasing our threshold of discomfort unlocks new experiences

Hey everyone 👋. Thanks for being a subscriber. If you enjoy the newsletter, please forward it and if you have 10 seconds to share a comment or an idea, hit reply! If you’re not already subscribed, you sign up for free to receive new posts and support:

It’s Monday morning and I’m currently at the Crater Lake Lodge siphoning off their lovely free wifi with a splendid view of the lake. I’m sitting inside instead of enjoying the great outdoors because I enjoy writing and have made it one of my key focuses. My main goal with writing is to not stop and I view the constraint of posting on Tuesdays as an appropriate amount of structure to enforce a cadence. The more things I try to do, the more I realize it’s actually really hard to juggle a bunch of things at once. It’s possible to sample many things at first, but eventually if you want go deep on something, it requires making tradeoffs. So that’s why I’m spending my most productive part of the day (the morning) writing and then planning to spend the remainder of the day wandering around Crater Lake before driving to Bend. Today, I’m writing about tolerating discomfort. These kind of topics can get a bit abstract and too metaphorical which is why I’m going to tie it together with the tangible story of summiting Mt. Shasta yesterday.

Summiting Mt. Shasta

On Saturday, after some morning yoga in the neighborhood park, paddle boarding and swimming across Castle Lake, then scrambling together some food and water, I started hiking towards Mt. Shasta at 5:49pm. Since this was my first time in the area, I already felt a bit stressed starting so late even though I knew it was going to be only a couple miles to the campsite. I arrived at 7:30pm at an elevation of 8,500 feet.

I wanted to travel light since I knew I would be exhausted coming down from the summit on the way back so I only brought one change of clothes. That was a mistake because I fell asleep still covered in sweat. I set my alarm for 2:45am, intentionally opting for the ‘Summit’ ringtone on my iPhone for the vibes. When I woke up, my shirt and shorts that I left spread out to dry on the tent floor were still wet. With my headlamp wrapped around my hat, I got moving by 3am and started hiking uphill because amidst the darkness, I didn’t know where the actual trail was. The day before, I was gathering some info in town and asked some locals about the hike. They described it as a slog which I gotta say is pretty accurate. This whole hike is one giant slog with varying textures of terrain (dirt, scree, boulders, snow). At 5am, dawn emerged and I turned my headlamp off. At 5:59am, as the sun was rising, I was still slogging up the same section of scree and it was so cold from the wind that my hands started to hurt. A few minutes later, I spotted a lost right-hand Outdoor Research glove which is the the definition of clutch. One cozy hand is better than zero cozy hands.

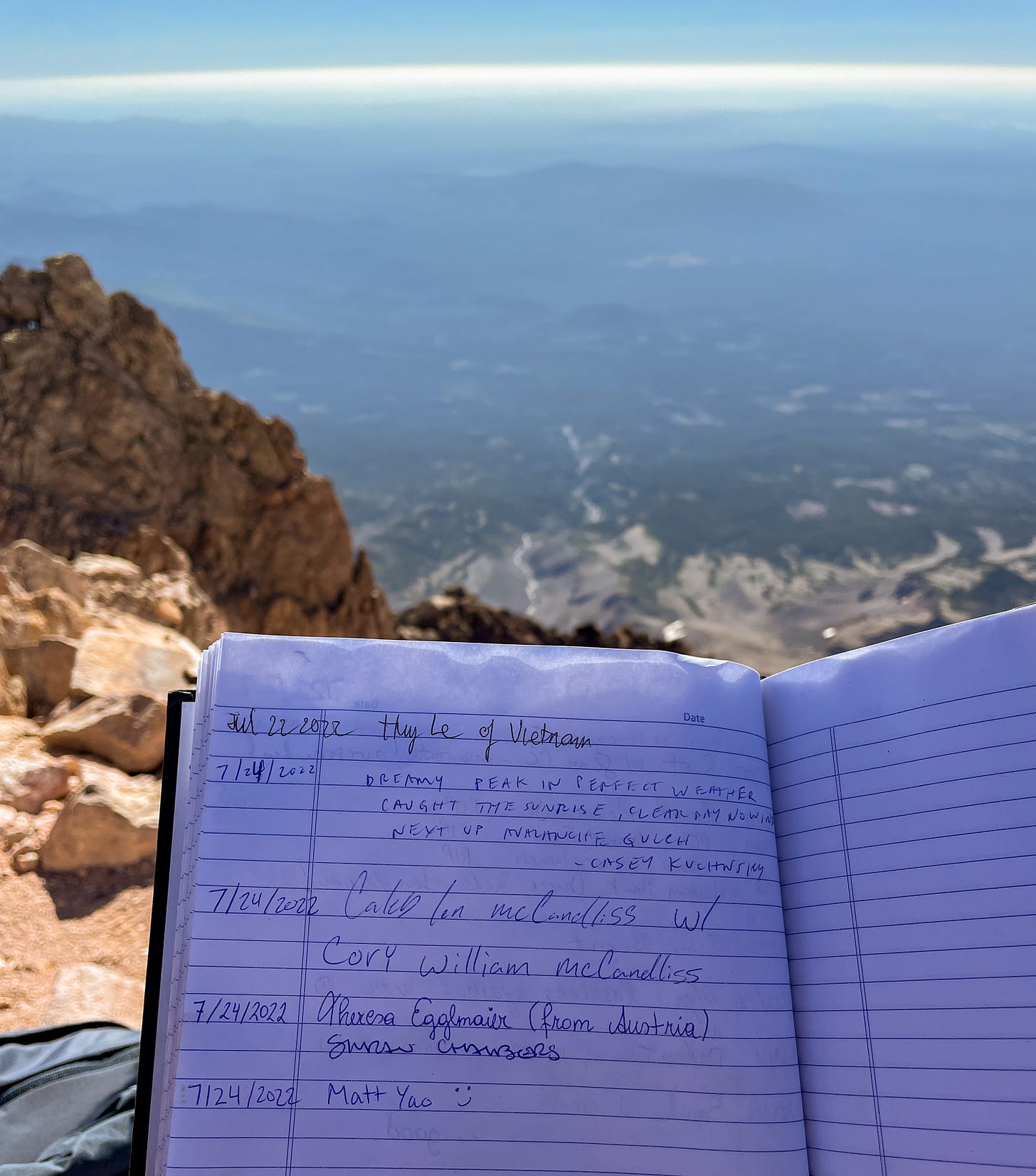

I summited (14,179’) at 8:52am and signed the logbook that the park rangers maintain in a heavy duty steel box. On the way down, my stupid $15 hiking poles kept shortening whenever I slipped on the loose dirt which led to falling on my back at least 10 times, but fortunately my backpack took the impact each time. By 1pm, I arrived back at my tent with a massive headache resulting from dehydration. I thought I brought enough water, but I underestimated how brutal the dry summer heat can be when there’s zero shade on the mountain. After packing up my tent and drinking some stream water, I started heading down. The hike down from the campsite is a steady downhill with a smooth path so you barely have to look down, but I was so exhausted that I kept scanning in front of me, looking for any tiny glimmer that would come from cars parked at the trailhead. At some point, I started hallucinating and seeing objects that looked like cars which were just trees. I got back to my car at 2:55pm, changed clothes, popped 3 Advils, and ate some pretzel chips (which tasted a lot saltier than usual because I sweated out a lot of salt and forgot to bring any salty snacks).

In the spirit of this post, I made a partial list of all the things that I didn’t want to do or didn’t find enjoyable:

researching what I need to bring, including ice axe and crampons and then finding which places sell them

spending two hours at REI getting a new backpack, a replacement tent bag, a new nozzle for my water bladder that’s partially broken, and new laces for my left hiking boot which could snap any day now

looking at AllTrails, reading blogs, and talking to a guide in town to get a sense of conditions

carrying my tent, sleeping bag, sleeping pad and then having to sleep in it

not being able to shower after hiking to the campsite and then sleeping covered in sweat

trying to fall asleep before you’re actually sleepy because you know you have to wake up at 2:45am

actually waking up at 2:45am

eating only bars (RX, Cliff, Kind) for an entire day

accidentally letting your backpack fall down which leads to your camelbak mouth piece gets covered in dirt and then having to still drink out of it because otherwise you’ll get even more dehydrated than you already are

having trouble breathing because there’s less oxygen at high altitude

Upon returning to my car, I briefly thought about why I wanted to summit Mt. Shasta. Maybe I did it for the views, adventure, stories to tell, exercise, being able to eat cookies and peanut butter cups guilt-free, or some combination of these. Even taking into consideration all the discomforts, I’m glad I did it. In some twisted way, it was fun and also made me think a lot about of tolerating discomfort →

I like comfort too

On the spectrum of tolerating discomfort which ranges from happily going weeks without a shower to can’t even spend a night away from home without their orthopedic memory foam pillow and 10,000 thread count Egyptian cotton bed sheets, I think I’m somewhere in the middle. I enjoy luxuries like massages and sometimes eating at fancy restaurants that list out dishes like “puréed nut spread paired with a grape relish reduction served on a brioche bun” when they could just say PB&J. I’ll shell out the extra dough for a comfy Lululemon hoodie and I even have some overpriced Aesop soap at home. I thoroughly enjoy the crisp white bed sheets at hotels that come with a duvet and then laying in bed with eight pillows and throwing seven of them onto the ground when it’s time to sleep. And nothing gets me more fired up than a decadent dessert like brownie a la mode.

Which is why it kinda bothers me when I’m talking to my non-outdoorsy friends about some recent hike or camping trip and they say they could never see themselves doing something similar because they don’t like the idea of sleeping inside a tent or not showering or having to eat camp food (whatever that may be). Why does it frustrate me? Because hidden in the rebuttal that they know they wouldn’t like camping or backpacking is the implication that I enjoy the same aspects that they dislike. They know that they dislike sleeping on the ground covered in sweat, getting bit by mosquitos, and eating mediocre-at-best meals. What they don’t seem to understand about me is that I also don’t like those things. I’ve had multiple conversations that have gone like “WOW, that’s so cool that you visited ____. I could never do that because I know I wouldn’t like camping. I like sleeping in my own bed too much.” Like a sommelier, I can sniff out the subtle undertones of them implying that I actually enjoy being covered in dirt, eating only protein bars for an entire day, or sleeping on an uneven surface inside a sleeping bag that’s too hot if fully closed, but too cold if left partially unzipped. If that were true, well then that would be dope because then the things I already do for fun would become even more enjoyable. But it’s not.

The pros outweigh the cons

The reason why I’m doing all this stuff like biking around Lake Tahoe, backpacking in Kauai, or summiting Mt. Shasta is not because I enjoy the unpleasant parts, but rather because I value the good parts more. Some might even describe those ‘good’ parts as great, amazing, otherworldly, or life-changing. It’s simple really - the pros outweigh the cons. Doing more and taking on more ambitious goals comes with two paths - increasing The Fun and decreasing The Suck. Making something more enjoyable could be as simple as buying a thick peanut butter cookie and saving it to enjoy at the summit of a hike (what I did yesterday) or going on a more adventurous hike that will give you amazing views. Reducing the unpleasant is the other way and includes things like using bug spray, buying a backpack with the proper fit and support, or hiring a guide to reduce risk and uncertainty. It’s the latter that I’m focusing on because finding more fun is easier and comes naturally. Decreasing The Suck is less obvious and is actually not about buying a bunch of things to make all your problems go away, but rather increasing tolerance of discomfort via experiences over time.

The threshold of tolerance

If assessing discomfort were quantifiable and determined with some sort of sensor that’s embedded in our mind and body, then I’d venture to say that my discomfort sensor is about as sensitive as everyone else’s. It’s not like my sensor is weaker or less sensitive to the stimuli.

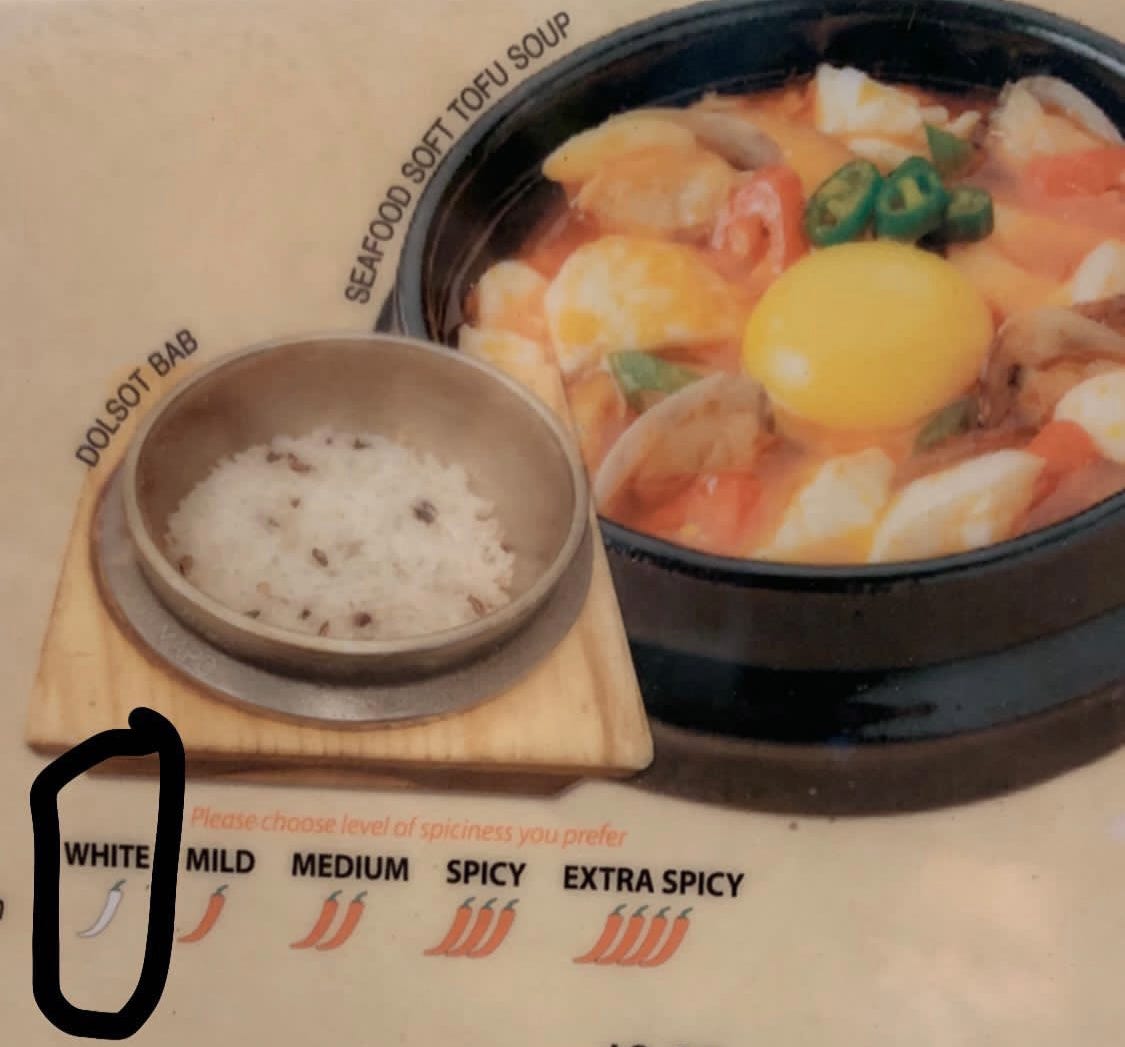

It all comes down to the threshold of tolerance which is how much discomfort you’re willing to take on as part of the experience. This doesn’t have to be all about me or about camping - those are just examples. Someone who can’t handle any spicy food and someone who can crush all ten wings in Hot Ones both have similar tastebuds. When a spice fanatic says “oh this isn’t spicy at all”, what they actually mean is “this level of spice is below my max spice threshold so I’m going to bucket it under the label of not spicy”. They can still taste the difference between a saltine cracker (no spice) and tabasco hot sauce (mild spice). It’s not like their tastebuds became dull or worn out from eating spicy food.

Someone might think the sleeping part of camping is a 4/10 on the comfort level and I would agree with them that it’s not that comfortable. If my discomfort sensor was somehow different, then I wouldn’t be able to discern the difference between sleeping on the ground outside and sleeping inside of a five star hotel room - but I can! The first time I went camping, I had a spacious tent with a huge sleeping pad and bag. I had the comfort and convenience of being next to my car and near a bathroom with showers. The second time, the bathroom didn’t have a shower. Then I got a smaller, lighter tent and sleeping pad. Each subsequent time, the comfort and convenience dropped slightly, but my tolerance increased more. Through subsequent experiences, my threshold of discomfort increased to the point now where I’ll sign myself up for multi-day backpacking trips.

Unlock new experiences

Going back to the spice analogy, people can gradually increase their spice tolerance by eating spicier foods over time. As their spice tolerance increases, the number of foods they can enjoy also expands. I can’t imagine living life without Thai or Mexican food and eating these dishes with the modification of no spice would be criminal. Of course, this analogy goes beyond just the spiciness of food. Simply put, there is quite a lot of dope shit out there that you have to endure the discomfort in order to experience. As your tolerance of discomfort increases, more opportunities appear to be within the realm of possibility.

Sometimes those things are unknown until you reach a certain threshold level because we don’t seek out or consider things outside of what we think is possible. An actual example is when I did this exact same Bay Area to Portland road trip in 2018. I’m doing the same route as last time, with the added stop at Shasta. How come I didn’t stop in Shasta last time? Well, it’s because I had probably did a quick Google search, read that climbing Mt. Shasta is the thing to do here and then quickly tossed away that idea because I thought I couldn’t do it. A couple months ago, when I made plans to be in Seattle, I remembered Mt. Shasta was on the drive up and only then started planning this hike. The key difference between 2018 and now is that I increased my tolerance for discomfort through a lot of hiking and camping.

By increasing our tolerance for discomfort, what used to be viewed as exceptionally difficult or unpleasant begins to become less important to us. We spend less of our time worrying about it and just accept that it’s part of the overall experience. Instead of viewing it as an optional, negative thing, it starts to resemble more of a mandatory, neutral task that we have to do just like any chore. And once that shift starts to happen, the new and cool experiences start to appear.

Have you ever been to a national park or any nature spot in general and found yourself surrounded by other tourists all clamoring for the perfect picture spot while passive aggressively jostling for position? It really takes away from the experience of being in the great outdoors when you have to be around a lot of other people. Especially the tourists that pour out of the buses with their family vacation t-shirts or those that take pictures using their iPad with their arms extended above blocking the view for everyone else. A concrete example is Yosemite National Park which draws in three million visitors per year and requires an hour drive from the nearest cluster of hotels in Mariposa to arrive at the valley. In this case, tolerating the discomfort of camping in the valley would allow you to start hiking earlier, beating the masses and avoiding the hottest hours of the summer day. By opting to camp, you could even wake up early for sunrise or stay out later for sunset, knowing that your place of rest is nearby.

When I think of how tolerating discomfort has led to fun memories in general, an obvious example is tolerating shitty flights. These flights are shitty in all kinds of ways. They could require long layovers, red-eyes, or just be really long. Back in the day, it was this tolerance of flying uncomfortably that resulted in more adventures. A few years ago, instead of taking a non-stop flight from San Francisco to Mexico City, I opted out for a red-eye that would stop in Chicago first in exchange for a $1,200 travel credit from United. Those travel credits paid for my next three flights which may not have happened otherwise. When I had less money, my friends and I didn’t let the cost of traveling stop us. We tracked flights, bought the cheap ones, stayed in hostels, and bought vodka from the FamilyMart across the street and drank it outside the club to avoid paying for drinks inside (fun in Thailand). Although now I sometimes book the more expensive flight if it’s non-stop and definitely don’t chug liquor on the streets anymore, I don’t view the past trips as filled with sacrifices or tough times. The common theme among the best trips has always been about maximizing The Fun rather than trying to minimize The Suck (the discomfort).

Three types of fun

This short, but sweet blog from climber and author Kelly Cordes analyzes the different kinds of fun. Type 1 is the most intuitive kind of fun because it’s fun while you’re doing it (like yummy food or surfing a wave). Type 2 isn’t fun while you do it, but fun in retrospect (any kind of running for me). Lastly, there’s Type 3 which shouldn’t even exist because it’s things that aren’t fun at all, at anytime. Cordes acknowledges “Into which category a given experience falls, of course, is highly subjective and highly subject to shifts (particularly from III to II) born of the rosy reflections afforded us by the passage of time.” My theory is that through increasing the tolerance of discomfort, you can even shift some things from Type 2 to Type 1 because the unpleasant parts that characterize it as Type 2 can eventually become viewed as negligible, peripheral, in the background. Type 1 fun is more accessible and well-known than Type 2 because even if you haven’t experienced the joy of eating at a world-class restaurant or surfing a wave, you know it’s fun. With Type 2, it’s less obvious to the outside and therefore rarer. It takes dipping your feet into the water to know what it feels like. I don’t think one is better than the other, but I do think Type 2 can be just as memorable and life-changing as Type 1 and we shouldn’t prevent ourselves from experiencing it by avoiding discomfort.

Life is short, go do stuff

Last Thursday, I spent the day in San Francisco and as I was walking back to the lot where my car was parked, I witnessed someone die on the streets. A police officer was giving them chest compressions, but their face was already pale. I didn’t know what to do and it was clear I couldn’t help given that there was already a crowd that was being shooed away. No more than a minute after I walked away, an ambulance whizzed by me and stopped at the scene. This might’ve been the first time I’ve seen someone die in person. It was a striking moment that woke me up a bit, but also left me feeling uneasy at how fleeting it was to walk by, not be able to do anything, and then go on with my evening. A reminder that life is not permanent and is characterized by quality of moments, not quantity of years lived. Here’s to hoping that an increased tolerance of discomfort will lead to new memories.

Cool note about the different types of fun! I’ve never thought to categorize them. Might be borrowing this :)